Iran - Travel Writing

Persian Hospitality

Nothing can prepare you for the nagging anxiety that pervades your body as you approach the Iranian border for the first time. Images of persecuted women, American hostages, and an old 'Ayatollah is a meanie' badge from my school days, swirled around in my mind in an endless stream of negativity towards the people of Persia. The reality was something else.

Two months earlier, as a leatherclad dispatch rider, I pushed open the heavy wooden door of the Iranian Consulate in London, under the watchful eye of the man in the bullet proof glass enclosure, with the video monitors. I stood nervously in the subdued hush, clutching a handful of papers and passports, to lodge a visa application. I approached the counter, painfully aware of my appearance, and handed over the forms to the upright and bearded gentleman behind the counter. Flicking sternly through the papers, he came to my New Zealand passport.

"Kiwi!" he exclaimed. "Anchor butter, good butter. And your lamb, very fine lamb sir. Where you from? Wellington? Auckland? " I couldn't believe my ears, and was soon discussing beautiful mountains and lush green grass, rather than religious preferences or politics.

However, my English partner was not so joyfully received. Salman Rushdie (an unfortunate last name I feel) had had lunch with the then Prime Minister John Major. A 5 day transit/tourist visa for British citizens had immediately risen from £25, to £500. A grim development when attempting to co-ordinate an overland journey from England to India on a shoestring. Three weeks later, and a week before our scheduled departure, the fee was dropped back to £25 again, a little closer to the £4 charged to 'kiwi'.

Visa's, and Carnet de Passage in hand, we now approached the Turkish/Iran border through the Kurdish strife torn region of north-eastern Turkey, butterflies fluttering.

Saskia, with the dodgy English passport, had bought a cheap, full length, rubberised Russian overcoat to satisfy the religious police, and had a selection of headscarves. I purchased a white collared, long sleeve shirt and tied my long hair back tight.

From the Turkish side of the border we could see bikers at the Iranian kiosk. Three Italians on two big trail bikes, a Suzuki DR800 Big, and a couple, on a Yamaha 750 Super Tenere. Our 83 BMW R100, heavily laden and covered already in a continents worth of crud and road grime, looked a little cumbersome parked beside them.

Able to share the confusion of paperwork as a group, helped the border formalities no end, and it was a all over in a couple of hours. Iranians in the queue were extremely helpful and informative, telling us the right order to approach the small windows, and on one occasion ordering back the crowd for us to go first. As the authorities perused the papers, Saskia quickly got talking to some local women, covered head to toe in black chadors, who laughed out loud at the thick overcoat in the 30 degree heat. Already covered in Shoshoni jeans, under a long skirt, leather jacket, and the old helmet over the head scarf trick. It was a bit over the top and we immediately gave away the obviously extreme attire.

In our two week crossing of the enormous country we were never harassed about our dress. Saskia's long skirt almost touched the ground, her long sleeved top wasn't tucked in, so none of her alluring curves were showing and always a head scarf. Always.

First village we came across, we braved our first petrol station. Unfortunately, before we'd seen a bank, to purchase Iranian Rials, and the little station didn't take Visacard. Luckily our new found companions, the Italians had plenty and offered to lend us some. As Mario walked back from the payment office he said " I'll cover it guys, you owe me one." Three tankfuls of high octane came to 90 cents American. We took turns, shouting each other tankfuls of gas over the next two weeks and several thousand miles, as we tackled the mammoth task of crossing Iran together.

The 7 days allocated by the visa to transit the country is limiting, and tends to keep overlanders on the straight and narrow route, in order to complete it in time. Luckily visa extensions were just a matter of popping into the Police Department of Alien Affairs, and showing off our culturally correct attire and beaming smiles, and paying the obligatory stamp fee.

Teheran is a big ugly sprawling city containing almost 20% of the entire population of Iran, surrounded by slums and filth that contain as many dangerous characters as any other city of her size. 'Knife pullers' as they were known locally. We gave her a wide berth like many big cities of the world and headed directly for the splendour and elaborate mosques of Esfahan.

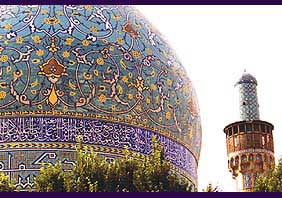

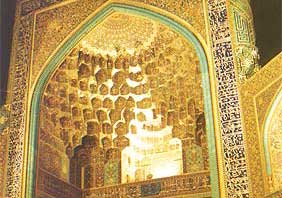

Isfahan has the greatest concentration of Islamic monuments in Iran, and the most glorious manifestations of Persian genius for art and architecture. Not to be missed is the Friday Prayer in Imam square. A square in the centre of the city surrounded by four of the most magnificent buildings in the world, the Sheik Lotfollah Mosque, the Ali Qapu Palace, Masjed-e Imam (Imam Mosque) and the great portal of the Qaisariyeh Bazaar. Thousands of locals gather and pray towards the southern end of the square every Friday evening, facing Mecca, and the architectural masterpiece of the Imam Mosque, with it's exceptional blue tile works and inlays, a majestic dome entrance and elegant minarets.

After prayer, the family groups assemble extravagant picnics on rugs with portable gas stoves. Women prepare food, men drink tea and smoke tobacco through hubbly-bubbly water pipes, while children run and play amongst the crowd, or take turns to play table tennis on the permanently placed concrete tables lining the centre of the square. It's a scene as beautiful and pure as the cover of a Jehovah Witness magazine, after the imminent destruction of the wicked.

Strolling through this serene environment, a large family, enjoying their picnic, beckons us to join them for food and drink. A young girl runs up behind us and places a small bouquet of flowers in my hand.

Tea was made and we shared the blanket with the eight children, of which the two eldest daughters spoke excellent English. The father was a local teacher and surprisingly spoke little English, but his wife continually stacked his water pipe with fresh coals and tobacco. He took long deliberate draws through the slender and colourful hose, and his broad smile would break out into bellows of laughter.

With Iran's links to world terrorist organisations and their well known hatred of 'the great Satan' , people often forget the real Iranians. Persian hospitality is second to none, the people are warm and friendly and genuinely interested in the foreign traveller, especially those from clean green New Zealand. Although this is perhaps principally because they don't see very many tourists at all these days.

When considering Iran's description of America as the great Satan, it's easy to forget that the Americans had a huge influence on the country for many years during the Shah's reign. They encouraged the Kennedy Peace Corp, a sort of exchange student scheme to promote and encourage the English language. Today English is widely spoken and often with a surprising American accent.

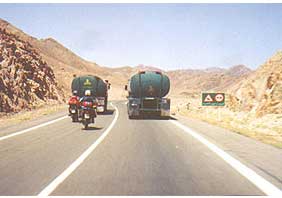

We left the oasis of Esfahan, and steamed across the wide open expanse of Iran's southern desert. The asphalt roads are black and wide, stretching as far as the eye can see across vast plains between treeless mountain ranges, whose colours constantly changed during the course of the day. Pools of black oil, swamp the ditches, from trucks performing cheap roadside oil changes to beat the effects of heat induced degradation.

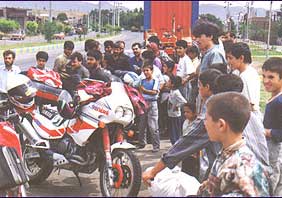

Kerman, a city in Iran's poorest region, at an altitude of 1800 metres, is a relatively cooler place. But not on the streets. The city had three choices of accommodation, a $200 a night American style hotel, one budget hotel and several bug riddled $1 a night pits for males only. One glimpse of the blood splattered walls was enough to discount them. But alas the budget hotel was full, and the flash one, well out of our meagre budget. While making an already difficult decision, a huge crowd of onlookers gathered round the disoriented bikers. It began to get dark.

A young boy, well spoken, complete with American accent started making conversation with us in front of the ever growing crowd. He wanted to practice his English and invited us to stay at his parents house. A timely invitation as the Iranian police pulled up in a couple of big 4x4's. The police began trying to disperse the huge crowd, an officer asked for our passports and inquired about our accommodation. The boy was looking a bit concerned.

"You people, follow us to the station. Boy, come with us."

We were escorted in a convoy of jeeps to a walled and fortified compound, asked to leave the bike outside, ordered to enter and the iron gate shut firmly behind us. The officer holding our passports disappeared down a dimly lit corridor. The boy was lead into an office and the door shut behind them. 45 nervous minutes later the man with the passports finally returned, fetching the boy from the office. Letters were presented for us all to sign, forbidding us to take up the boys offer of hospitality. Passports back I safe hands, we were slipped back out into the dark and empty streets. Funnily, in the same dilemma we were in two hours previous, only now it was pitch black as well.

"Bugger this place, lets just get the hell out of here."

We rode out of the city lights onto the vast plains. Melon stalls lined the busy highway, and we pulled into a deserted one. Under cover of darkness we lay dry palm fronds over the bike, careful to cover the reflectors, and curled up under the bike in the dust. Mice scurried under the our sleeping bags and rug. Fleas and late night trucks meant very little sleep. Up before the sun, we blasted across the empty plain, sitting on 100mph for over an hour, attempting to blow away the nightmare.

By 11 o'clock the temperature, according to the thermometer around Saskia's neck was over 42 degrees Celsius. We took shelter in a shady restaurant for an early omelette lunch.

Getting ready to leave, Saskia noticed her sunglasses were missing from the table. We gave chase to two Iranians seen wandering through the parched thorny scrub out the back of the brown mud brick building. Their tracks were lost and on returning to the table, we began arguing with staff. We made it clear we were patient people, and weren't leaving without them. The building was thoroughly searched over and over. Toilets were searched. A waiter returned from cubicle three, his arm coated up to his elbow with muck, glasses in the other hand, having fished them out of the squat style long drop toilets.

To her passing day she remained unsure of which cubicle she had actually visited.

Zehedan, a city in the far south-east, is the gateway to Pakistan, and the frontier border town of Mirjaveh. Thorough custom checks take place, with particular attention being paid to carpets and rugs. Abruptly, the smooth world class motorways of Iran, turns to 60 kms of corrugated desert track 50 metres wide and subject to sand drifts, trucks, buses and brand new Toyota hilux's, full of turbans, weapons and the occasional camel.

In the Pakistani immigration office, the officer casts his gaze towards the European women present.

"You can remove your headgear madams, you are in Pakistan now. Welcome."

Imam Mosque, Isfahan.

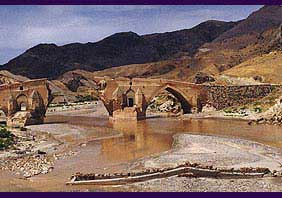

Old bombed bridges next to new.

Instant rent-a-crowds.

Petrol at 90 cents a tankful.

Masjid-i Shah, Isfahan

Extravagant picnics on rugs.

The Great Satan.

Children of Bam

Signs says 'no overtaking'.

42 degrees Celsius before midday.

Pakistani bus bohemoths.